| THE CHICAGO SUN-TIMES,

SUNDAY SEPT. 3, 2000

|

||

|

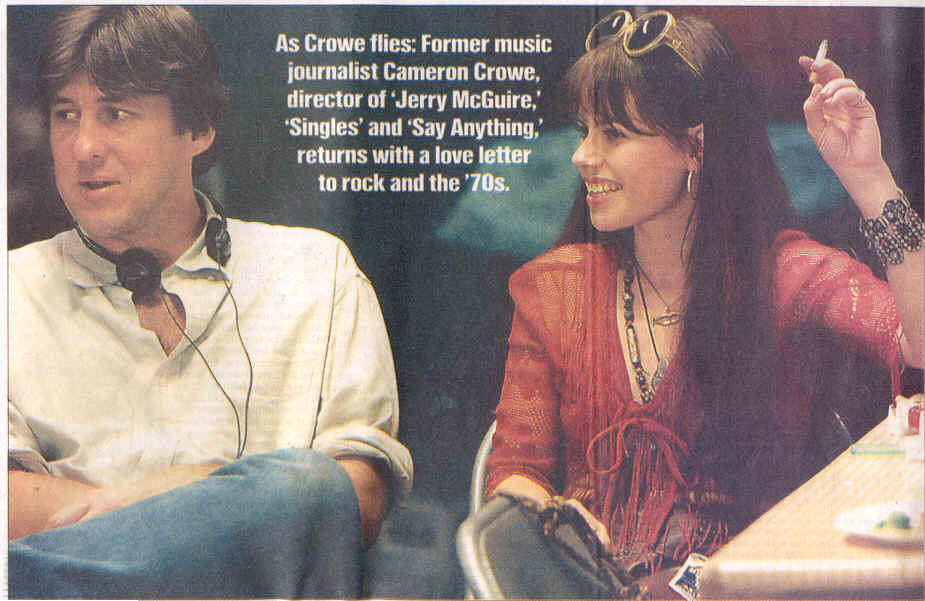

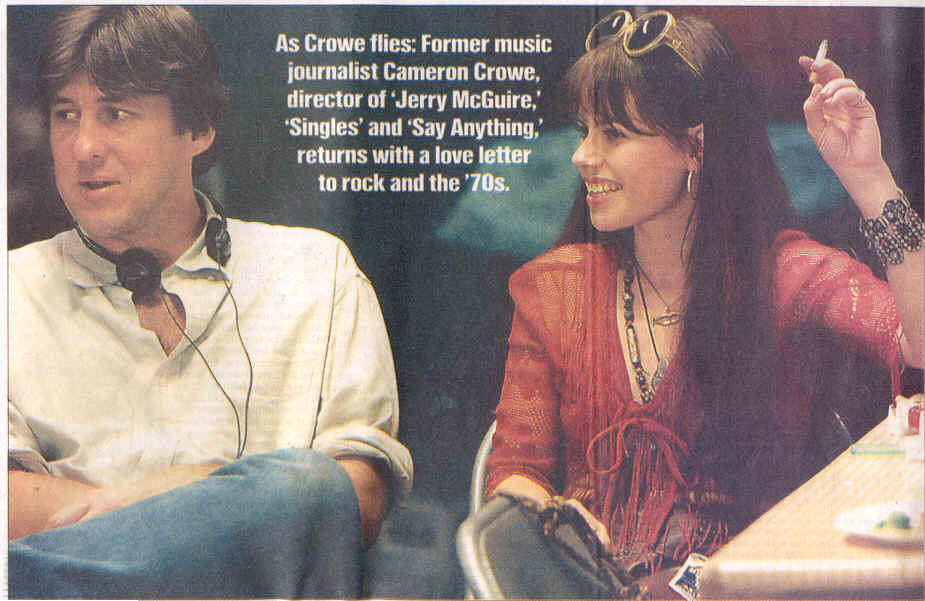

As Crowe flies

September 3, 2000 BY JIM DeROGATIS pop music critic LOS ANGELES--As I arrive in an editing studio on the Fox lot in Hollywood, the beautiful, melancholy sounds of "The Rain Song" by Led Zeppelin are blasting on the soundtrack. The dramatic strum of Jimmy Page's guitar merges perfectly with the image onscreen of actor Patrick Fugit (portraying William Miller, a k a the young Cameron Crowe) collapsing on his bed, exhausted. The scene shifts to Fairuza Balk, one of a gang of groupies known as "Band Aids." The music swells majestically as she tosses her long black hair. It's a key point near the end of "Almost Famous," Crowe's new film, and Balk is having a conversation with Billy Crudup, the actor who plays Russell Hammond, the vainglorious leader of a fictional '70s rock band called Stillwater. "You don't even know what it is to be a fan," Balk says. "To truly love some little piece of music so much that it hurts." Crudup stares into the distance, pondering her words. The music sighs, the scene ends, and the technicians stop the film. "Niiiice," Crowe says with just a hint of a Southern California surfer accent. "Very nice!" It's early July, 10 weeks before the movie's Sept. 15 opening, and it's the last day of six intense weeks of sound editing, the final step before the film's completion. Three recording engineers--one for dialogue, one for music and one for sound effects--plus music rights consultant Danny Bramson and numerous assistants busy themselves behind a giant console that looks like the control panel for the starship Enterprise. "This is the `Jerry Maguire' crew," Crowe explains. Like ballplayers at the end of the season, they are slightly giddy as they make the final fixes on the eagerly awaited followup to Crowe's 1996 hit. The director smiles and lapses into a bit of "Blues Brothers" shtick. "The band got back together!" he says. "The man wanted to keep us apart, but we got together again!" All of the movies that Crowe has written, or written and directed--"Fast Times at Ridgemont High" (1982), "The Wild Life" (1984), "Say Anything" (1989), "Singles" (1992) and "Jerry Maguire"--are marked by their extraordinary use of music, which isn't surprising, given his background as a rock journalist. Now 42, the director was a 15-year-old Catholic high school kid from San Diego when he began covering bands such as Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin and the Eagles for Creem and Rolling Stone magazines in 1973. "Almost Famous" tells the story of his first year on the road. Tall, gangly but otherwise inconspicuous, Crowe quietly absorbed everything around him during seven of the headiest years in rock history, then set it down on paper with the enthusiasm of a diehard fan. He employed a similar modus operandi a few years later in 1979 when he re-enrolled in high school, posing as a senior at age 22 to write a book about how "the kids" really lived. Fast Times at Ridgemont High became a best seller, which led Crowe to write a screenplay for the film by Amy Heckerling. Though it flopped on release, the movie became a huge hit on video, making stars of cast members such as Sean Penn, who portrayed stoned-out surfer Jeff Spicoli. Crowe's movie career was launched, but it would be a constant struggle to make films the way he wanted, in the warm romantic-comedy tradition of his hero Billy Wilder. (Alfred A. Knopf recently published his book of interviews with the director of "The Apartment" and "Some Like It Hot.") "The only movie that I've ever been a part of where the money guys `got it' was `The Wild Life,' " Crowe says, referring to his least successful film. "I'm used to them not getting it. They didn't get this movie; they didn't get `Jerry Maguire'; they definitely didn't get `Singles,' and `Say Anything' was barely released. In many ways it's a miracle that we're even sitting here talking about my work in film, because the only stuff that wasn't a battle for me was rock journalism." Music clearly remains Crowe's first and truest love. Balk may be doing the talking in the scene described above, but the sentiments are the director's. "We tried a lot of songs in that scene," Crowe says. "We really wanted to hit her speech about being a fan--that feeling about it being your band and loving a song like `The Rain Song,' which could make you cry on the right occasion. It was all about that speech, and unless you honored that speech by putting the right music behind it, it was just a candidate to be cut, as opposed to the heart of the movie." Trivia fact: "Nothing Man" by Crowe's friends Pearl Jam was the song that Crudup was actually listening to as the scene was filmed. "Other directors say you have to be careful with people listening to music on the set because it could look good while you're filming but later it might not sync up," Crowe says. "I disagree. The look of someone listening to music they love is a unique look, and I wanted to capture that. "The whole subject matter is just so personal and fascinating to me. Another guy would be interested in car racing or something. It's all about what you're a fan of. It's almost punk-rock, trying to push a personal movie through the mainstream pipeline. You have to have had a movie like `Jerry Maguire' for people to trust you and let you make a movie like this and cast it the way you want to cast it, without any stars." "Almost Famous" was the most difficult of Crowe's films to make because it was the most personal and because he felt an obligation to accurately capture real-life characters like his rock-critic mentor, the late Lester Bangs. "I was in denial that I was actually doing the movie for a long time," Crowe says. "I thought there was a real danger of doing a `glory of me' project. I really have a problem with talking about myself; my taste is for utterly personal stuff that doesn't revel in the glory of ego. It's like the blowhard at the party whose voice is too loud. I really wanted to avoid that, and all my friends will tell you that I tortured them and tortured myself deciding to finally do this." As in the past, music provided the way into the project. The director started making "road trip tapes" full of the music of the era, and those inspired him to start writing. It's a cardinal rule of the movie business that the screenwriter never specifies what music will be playing during a scene, but Crowe ignored this convention even before he started directing his own films. "The scripts--all of them, even `Jerry Maguire'--start with the music for me," he says. * * * Twelve hours later, after lunch at the commissary and a break for a dinner of Indian takeout, the crew is beginning to hit the wall, but Crowe shows no signs of slowing down. Chronically described as "boyish" (even now, long after his days as a wunderkind), he is constantly pacing behind the mixing console, tossing a baseball in the air, answering questions from his assistants, pausing to check his email on a laptop and talking to this reporter all at once. It's as if he's urging his team toward the finish line by his own display of perpetual motion. Crowe's wife, Heart guitarist Nancy Wilson, has arrived in the studio to add a bass line to the score during another key scene, the one where Fugit/Miller bids farewell to the groupie who has stolen his heart, Kate Hudson as Penny Lane. The crew gives the impression that they think things are just fine as they stand (and they'd really like to go home), but Crowe is convinced that Wilson's bass will put the scene over the top. The couple fell in love during the making of "Fast Times," after being set up on a blind date by two mutual friends, rock photographer Neal Preston and Kelly Curtis, the manager of Heart and Pearl Jam. "Nancy just didn't know how uncool it was to date a rock writer," Crowe jokes. Since then, Wilson has written the scores for all of his films. In between taking care of their young twins, she also penned several of the songs that Stillwater performs, utilizing a style that evokes bluesy mid-'70s rockers Bad Company. "We have the same musical taste, and we speak shorthand," Crowe says of working with his wife. "Everybody does these scores that are keyboard-based, because it's easy; you can sample everything on keyboard. I like guitar scores; it sort of suits my writing better. I can walk in the kitchen and say, `Let's do a romantic theme on guitar,' and she'll say, `I'll do it later.' I'll say, `Now, now, now!' and she'll sit down and play something that becomes like the theme of `Jerry Maguire.' " "It's really his voice and his taste in music," Wilson says as she tunes her bass and waits for the engineers to roll the tape. "He gets a lot of his inspiration from listening to songs and cutting out pictures--it's kind of like a collage effect with music, where there's like an ache or something and he hears the song and gets into the story. We're roughly the same age, and we have a really similar background with the stuff we loved in music--Dylan and the Beach Boys and all that stuff. He was like the only guy I ever met who had such similar taste in music." "Quiet on the set!" somebody shouts, and the crew begins rolling the film and recording Wilson's bass part. The musician watches the screen as Fugit runs along an airport concourse, keeping pace with Hudson's plane as it taxies down the runway. The spare but touching score underscores both the connection and the distance between them. As their actors' eyes meet, the musician hits a rolling bass note that does indeed bring the moment to its emotional climax. The note is still ringing in the air when the engineers stop the film and turn expectantly toward Crowe. "Niiiice!," the director says, even more enthusiastically than before. "Very nice!" Everyone applauds for "one-take Wilson," no one clapping louder than Crowe. The last of the sound fixes has been completed, and the director is ready to send his film into the world. *** Great moments by the numbers A few years ago, Cameron Crowe was decrying what he called "the Batman syndrome" of big-budget movies slapping pop songs on the soundtrack as a marketing gimmick, regardless of whether or not the music fit the film. "That's the case less and less now," Crowe says. "It's just a different generation of filmmakers coming up, and what was once the shining example--Martin Scorsese and the way he used rock music in his movies--is now becoming more and more common." Every fan of Crowe's work has a favorite music-movie pairing from his films. Here are some of mine, as well as the director's choices, which may be surprising. * "Fast Times at Ridgemont High" My choice: The scene where Mike Damone lectures Mark "Rat" Ratner on side two of "Led Zeppelin IV" as perfect makeout music. Ironically, "Kashmir" from "Physical Graffiti" plays on the soundtrack--at the time, it was the only Zep song that Crowe could get the rights for. Crowe's choice: " `Somebody's Baby' by Jackson Browne--definitely the scene with `Somebody's Baby.' " * "Say Anything" My choice: John Cusack as Lloyd Dobler tries to win Ione Skye's Diane Court by playing Peter Gabriel's "In Your Eyes" on a boom box held aloft in the rain. Crowe's choice: " `Within Your Reach' [by the Replacements], when Lloyd is packing to leave home. I love that." * "Jerry Maguire" My choice: Tom Cruise as Maguire banging the steering wheel in time to Tom Petty's "Free Fallin'," oblivious to the fact that that's exactly what he's doing. Crowe's choice: "It would be [Bruce Springsteen's] `Secret Garden,' when Rene [Zellweger] runs down the street, and just before that when she sees her little boy kissing Tom. It's one of my favorite moments as a director. I also like `Magic Bus' [by the Who] at the beginning. It set the tone for the whole movie." * "Almost Famous" My choice: Philip Seymour Hoffman as Lester Bangs doing the chicken dance to "Search and Destroy" by the Stooges. Crowe's choice: "Led Zeppelin's `That's the Way.' And I really like Bloodwyn Pig in this movie. And I liked finding `Your Move' [by Yes] for when the kid gets backstage for the first time, because that felt kind of quietly triumphant. But the new one is totally built on the music--it's all about the music." Jim DeRogatis *** Bangs served as role model for filmmaker A s a precocious 15-year-old, Cameron Crowe began writing about rock music for the alternative weekly the San Diego Door. His editor was Bill Maguire--the director would pay homage when he chose Jerry Maguire's surname 22 years later--but his real role model was rock critic Lester Bangs, who grew up in nearby El Cajon, then moved to Detroit to edit Creem magazine. Bangs returned home to visit at Christmas 1973. Crowe stood outside watching through the plate-glass window as his hero did an interview on an FM rock station. Afterward, the two went for a hamburger. Bangs had read the clips Crowe sent him, and he rewarded him with an assignment to interview Humble Pie. This scene is recounted in "Almost Famous" as Bangs is portrayed by the red-hot method actor Philip Seymour Hoffman ("Boogie Nights," "Magnolia," "The Talented Mr. Ripley"). He is the moral conscience of the movie, the wise sage who tells the young Crowe not to befriend rock stars and to always be "honest and unmerciful." (Never mind that Bangs sometimes ignored his own advice.) I met Bangs a decade later, two weeks before he died in the spring of 1982, when I was a senior in high school. Crowe read a fanzine article that I wrote about my encounter, and for years, every six months or so, he called and encouraged me to write a book about Bangs' life. Eventually I did. (I contributed research material to "Almost Famous"--although I was not a paid or credited consultant--and Crowe was one of more than 200 people interviewed for my book.) I asked the director to talk about why Lester Bangs was so important to him and to so many of our fellow rock writers. "What your book is about, what my movie is about, what Lester Bangs is about is being a fan," Crowe said. The biggest thing was--with all due respect to Lester--not to write a movie that was a tribute to Lester, but to make a movie that was a tribute to the way that music makes you feel. If you can get the movie to make you feel like a song you just sort of discovered that you want to hear like eight times in a row, that's the hardest thing. Part of that story is a guy who can grab you by the collars and say, `Listen to this!' or `Don't hang out with rock stars!' Of course, you have to embrace the contradictions, because fully half the time I spent with Lester was hanging out with rock stars! "I was intent on capturing Lester's humor. Hoffman was listening to a tape of your interview with Lester in between takes, but that was the 1982 Lester, and I wanted to make sure he was connected to the '73 Lester. The push and pull of our discussions and the performance created a more truthful Lester because you have the humor and you also have the darkness that was obvious just by looking at his body: He seemed gloriously toxic. Hoffman caught the soul, I fought for the humor, and the collaboration surprised us both. "When [DreamWorks studio chief Steven] Spielberg saw the movie, he called me up--and believe me, I don't get many calls from Steven Spielberg--and he said, `I'm gonna quote Lester Bangs to you right now and I'm gonna be honest and unmerciful.' He told me what he thought of the movie and he was very complimentary and also very laserlike about pace and stuff. I had about 30 people read the part of Lester, including Tom Cruise. In the end I hired the one guy who didn't even read--he just walked in and started talking about this American Express ad that he'd seen with one of his heroes up on a bulletin board, and it was a very Lester-like rant. But I hear Lester laughing in those moments, when I hear Cruise reading his words, or when Steven Spielberg quotes him. "If the both of us, through our own experiences with Lester, have found a way to start a debate about the state of rock criticism or at least bring attention to this guy via your book or my movie, I say let it all come, because he really deserves it." Jim DeRogatis *** Screenplays spawn imitators F rom Jeff Spicoli's immortal words, "People on 'ludes should not drive," to Rod Tidwell's timeless exhortation, "Show me the money!," Cameron Crowe has shown a remarkable ability for crafting catchphrases and tapping into the cultural zeitgeist. For evidence, you need only look at his imitators. "Arli$$," an HBO series about a funny and aggressive sports agent, premiered several months after the success of "Jerry Maguire," Crowe's film about a funny and aggressive sports agent. "They say `Arli$$' was in development before they knew about `Jerry Maguire,' but who knows?" Crowe says. After Crowe's 1992 movie "Singles," Warner Bros. Television asked him to turn the film into a TV series about a group of six 20-something roommates searching for love. Crowe declined. Several months later, ABC's fall schedule was announced, and it included a show called "Singles" about a group of six 20-something roommates searching for love. Crowe's attorneys moved into action, but the show's producers said it was all a big mistake, and their show was actually "Friends." When the TV show premiered, several details seemed familiar: There was the gang frolicking in the courtyard, hanging out at a coffeehouse and listening to a goofy musician singing about a cat. "I had my lawyer look into it and it turns out that they had changed just enough of the details so that it would be not an easy lawsuit," Crowe says.(A Warner Bros. spokesman declined to comment.) Imitation has its upside. How does Crowe feel when a phrase like "Show me the money" becomes ubiquitous in pop culture? "I love it," he says. "I loved it when it came up at like the Westminster Dog Show--that was the most fun thing ever. It's never the one you intend it to be. Every time you try and write a catchphrase, the audience is smarter than that, they can hear the typewriter behind it. It's like every Clint Eastwood catchphrase after `Make my day'; the poor guy, you can see him struggling. There's nothing more fun than discovering your own catchphrase, and nothing sadder than getting one forced on you." Jim DeRogatis

|

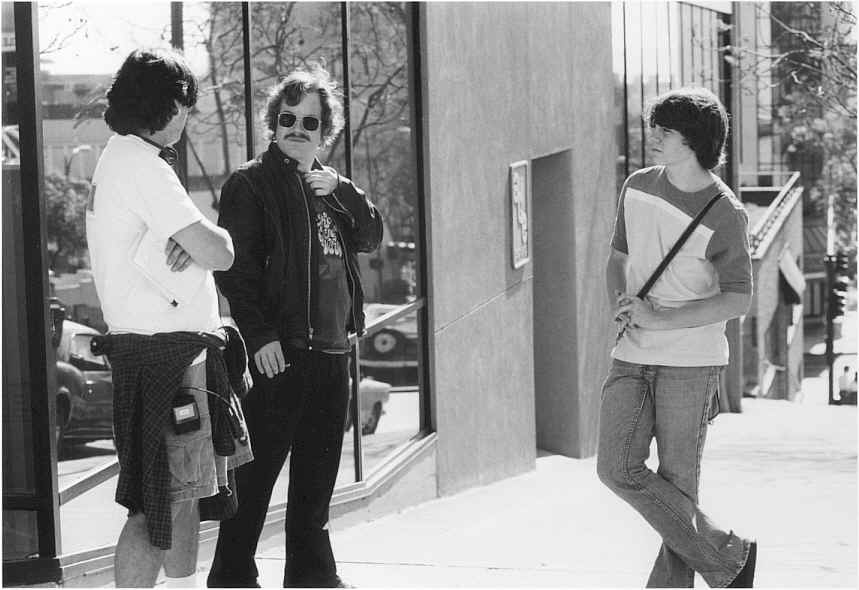

Cameron Crowe, Philip Seymour Hoffman, and Patrick Fugit. Photo by Neal Preston, courtesy of Cameron Crowe and Almost Famous. Copyright reserved.

Cameron Crowe on location in San Diego with Philip Seymour Hoffman as Lester Bangs and Patrick Fugit as William Miller (a.k.a. the young Crowe).